Japan Passes Bill to Make Online Insults Punishable by Jail time

A bill to introduce prison terms as part of tougher penalties for online insults was passed Monday at an upper house plenary session, marking a major step toward tackling cyberbullying in Japan.

Moves to amend the country’s Penal Code gained traction after Hana Kimura, a 22-year-old professional wrestler and cast member on the popular Netflix reality show “Terrace House,” was believed to have committed suicide in May 2020 after receiving a barrage of hateful messages on social media.

The parliamentary debate has centered on how to strike a delicate balance between tougher regulations and freedom of expression as guaranteed by the Constitution.

The main opposition Constitutional Democratic Party of Japan and others have opposed the revision, arguing that it could stifle legitimate criticism of politicians and public officials.

The bill was passed after reaching an agreement with the ruling Liberal Democratic Party that a supplementary provision, stipulating that a review will be conducted within three years of its enactment to determine if it unfairly restricts free speech, would be added.

In Japan, insults are distinguished from defamation in that the former publicly demeans someone without referring to a specific action but both are punishable under the law.

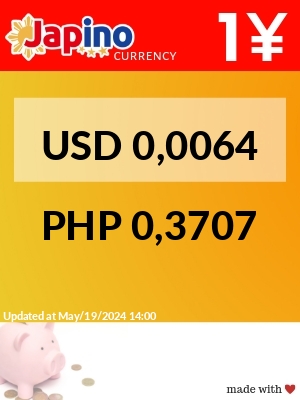

At present, the penalty for insults is detention for less than 30 days or a fine of less than 10,000 yen. The proposed amendments will introduce a prison term of up to one year and raise the fine to up to 300,000 yen.

The statute of limitations for insults will also be extended from one year to three years. The changes will come into effect 20 days after their promulgation.

The degree to which an insult will be considered punishable under the legislation remains unclear.

Two men in Osaka and Fukui prefectures were fined 9,000 yen each for insults posted about TV personality Kimura before her death, but some expressed concern the penalties were too light which led to the push for the legal changes.

Also Monday, a proposal to unify two types of imprisonment — with and without forced labor — into a single punishment was passed at the plenary session of the House of Councillors.

Prison work will no longer be mandatory for inmates, allowing more time to be allocated for rehabilitative guidance and education in efforts to reduce recidivism.

The establishment of the unified imprisonment law will take effect within three years of its promulgation. It marks the first time changes have been made for this type of punishment since the Penal Code was enacted in 1907.