PHILIPPINES: As Pandemic Eases, More Filipino Nurses Set to Seek Work Abroad

More Filipino nurses, attracted by higher salaries abroad, are set to leave their country as coronavirus border controls ease and hiring becomes more aggressive, putting the Philippines in a tight spot in dealing with its own shortage of health care workers.

President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. in September said he wants to increase the cap on the number of nurses allowed to go abroad annually from the current 7,500, but that the government at the same time must strive “to improve opportunities domestically.”

The cap is a policy the Philippines implemented in 2020 to retain enough nurses to fight the pandemic at home. It has since been eased in stages.

Philippine nurses fluent in English are in high demand overseas. As of the end of 2021, over 310,000 of more than 910,000 registered nurses in the Philippines were working abroad, according to an advocacy group called Filipino Nurses United and the Health Department.

Between 13,000 and 22,000 nurses had previously migrated annually to more developed countries, such as Australia, Britain, Germany, Japan, Saudi Arabia and the United States, where they could earn significantly more.

In 2020 and 2021, following the introduction of the cap, the combined number of nurses who sought employment abroad decreased to 16,391. And yet, the Health Department said in September that the Philippines still lacked over 100,000 nurses.

Philippine Nurses Association president Melvin Miranda said low salary and poor working conditions had been an issue for so long but became more apparent during the pandemic as hospitals saw a high turnover of nurses.

Miranda said Filipino nurses continue to be the lowest paid with a monthly salary of $687, compared with their peers in other Southeast Asian countries like Vietnam ($1,083) and Singapore ($4,058) based on a 2020 study by data aggregator iPrice Group.

The nurses association is pushing to amend the 20-year-old nursing law and standardize nurses’ wages and benefits, like overtime and hazard pay. Miranda said the Philippines might not be able to match the rates in Singapore or in the United States, but it somehow needs to catch up.

To dialysis nurse Kristine Joyce Barruga, 31, a salary “four to five times higher” and better working conditions were her reasons for leaving Manila in October.

“The pandemic was one of the reasons I felt strongly about going to the U.K.,” she said. “We worked 16 hours straight wearing the PPE because we were understaffed. There was no public transportation (so) some of us had to stay in the hospital for weeks. I love what I do but that was just exhausting.”

Filipino nurses are in demand in countries with an aging workforce, said Elnora Villafana, a service recruiter in Manila. She said they expect the nurse outflow to increase, as she also observes hospitals, specifically in the United States, becoming more competitive by paying for the licensing exams of the nurses and by dangling immigrant visas.

Nurses in the United States can make $70,000 per year.

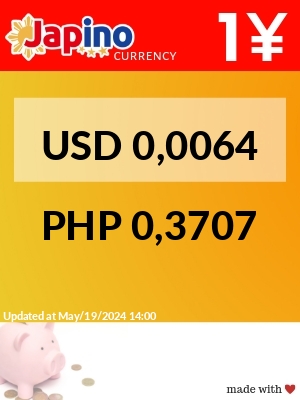

In countries like Japan and Germany, an additional year of language training discourages some nurse applicants, another recruiter Marivic Ochoa said.

But not Jan Yago, a junior nursing student and an anime fan. He plans on moving to Japan right after gaining two years of clinical work experience, which is a requirement in every foreign country.

“The pay (in the Philippines) is quite dismal,” Yago said. “I’d like to go to Japan, but once I have enough savings to support myself and my family, I’ll come back to the Philippines,” he said.